As Indigenous peoples, we have long lived in harmony with nature in one of the last undisturbed tropical forests in Panama. For centuries, we have relied on rivers for sustainable transportation and view the forest as our natural pharmacy, providing access to medicinal plants at any time. One of our primary goals is to strengthen our cultural traditions related to environmental protection, water conservation, agriculture, and coexistence with the land.

Biodiversity in Panama

Despite covering an area slightly smaller than the U.S. state of South Carolina, the S-shaped isthmus of Panama is one of the most ecologically vibrant and biodiverse regions on Earth. As a land bridge between North and South America, it has served as a vital biological corridor since the Great American Biotic Interchange, an event that initiated the north-south migration and genetic mixing of countless plant and animal species around 2.7 million years ago. Additionally, the emergence of the isthmus divided the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, setting numerous marine species on divergent evolutionary paths.

Located at tropical latitudes between Costa Rica and Colombia, Panama is a hot, humid country characterized by an extended wet season (May to December) and a comparatively short dry season (January to May). A rugged mountain range divides the interior into two distinct watersheds: the Pacific and the Caribbean, with the latter experiencing a significantly wetter and less predictable climate. The varied physical geography and intense climatic conditions have fostered a rich diversity of lush ecosystems in Panama, including lowland tropical rainforests, vibrant wetlands, coastal mangroves, dry forests, and high-altitude cloud forests. Nearly 500 rivers crisscross the country, while approximately 1,600 islands and islets, many adorned with kaleidoscopic coral reefs, dot its white sand shores.

Thanks to its remarkable array of ecological niches, Panama is home to an exceptional variety of biological life. Approximately 11,000 plant species, including 1,200 orchids and 1,500 tree species, nearly 1,000 bird species, over 200 species of amphibians, and more than 200 species of mammals thrive in Panama, many of which are endemic, rare, and globally threatened. Its charismatic fauna includes jaguars, sloths, Baird’s tapirs, monkeys, harpy eagles, resplendent quetzals, neon-colored poison dart frogs, and five species of sea turtles, to name just a few. As a hub for migratory bird life, Panama attracts thousands of hawks, eagles, and other birds of prey during an impressive annual raptor migration.

Conservation and Sustainability

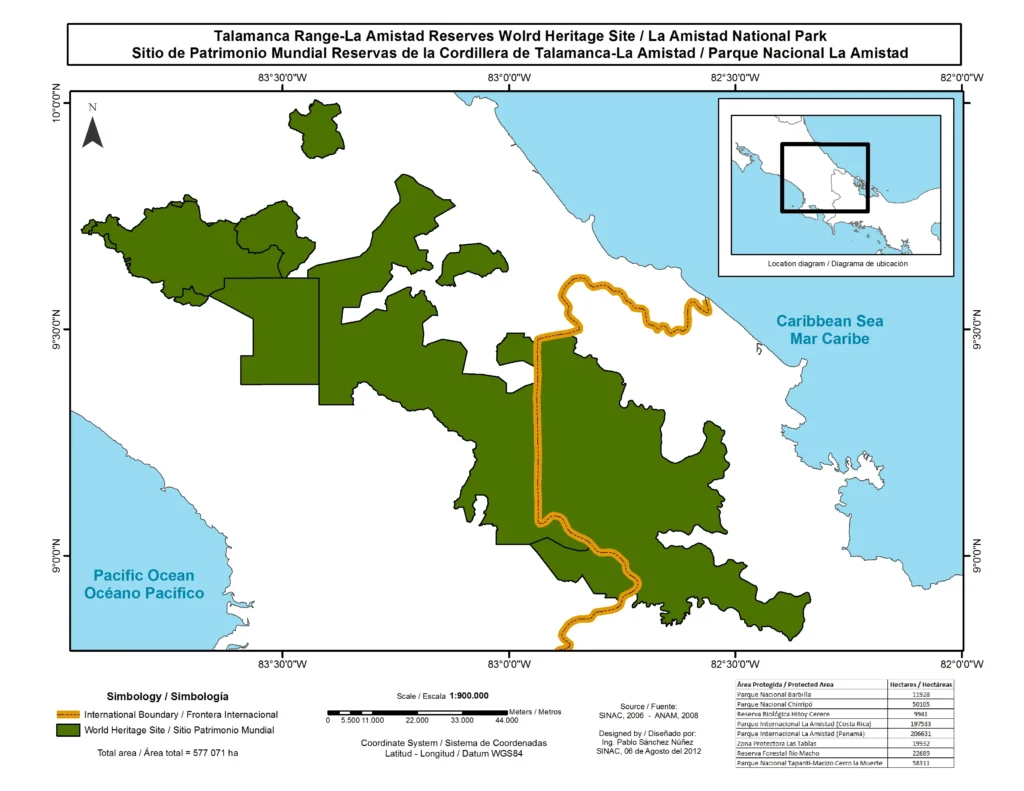

Although Panama has lost more than half of its tree cover since the 1940s, conservation and sustainability are now recognized as essential components of the national agenda. To date, the Panamanian government has designated approximately 3.5 million hectares—nearly 40% of its territory—as legally protected areas, including 13 national parks and marine zones. Three of these reserves hold global significance and have been designated as UNESCO World Heritage sites, including La Amistad International Park in Bocas del Toro province, which is jointly administered by Panama and Costa Rica.

La Amistad National Park extends along the border between Panama and Costa Rica. The transboundary property covers large tracts of the highest and wildest non-volcanic mountain range in Central America and is one of that region’s outstanding conservation areas. The Talamanca Mountains contain one of the major remaining blocks of natural forest in Central America with no other protected area complex in Central America containing a comparable altitudinal variation […] The beautiful and rugged mountain landscape harbours extraordinary biological and cultural diversity. Pre-ceramic archaeological sites indicate that the Talamanca Range has a history of many millennia of human occupation. There are several indigenous peoples on both sides of the border within and near the property. In terms of biological diversity, there is a wide range of ecosystems, an unusual richness of species per area unit and an extraordinary degree of endemism.

— UNESCO World Heritage Convention

Environmental Risks

Despite significant progress in environmental protection, Panama’s natural landscapes face numerous threats, largely due to a development model that prioritizes economic growth over environmental sustainability and a philosophy that places “man against nature.” For instance, plans to develop the nation’s Caribbean coastline, such as La Conquista del Atlántico (The Conquest of the Atlantic), aim to open the region to new forms of exploitation. Activities such as open-pit mining, logging, ranching, tourism, and real estate development have all contributed to the degradation of Panama’s natural wealth. Ongoing environmental issues include habitat loss, water pollution, soil degradation, wildlife trafficking, and anthropogenic climate change. Additionally, Panama’s environmental agencies are chronically underfunded and, in some cases, politically compromised.

Indigenous Stewardship

The Ngäbe and Buglé peoples possess invaluable ethnobiological and ecological knowledge of Panama’s forests, which should be recognized by our political and scientific communities. As vulnerable stakeholders whose health and livelihoods directly depend on the integrity of our natural resources, we must be included in all high-level discussions related to conservation and development, both locally and nationally. Unfortunately, this is often not the case. A key aspect of MODETEAB’s work is to raise public awareness of Panama’s rich natural heritage, defend it from reckless destruction, and promote our Indigenous peoples as the best stewards of this land.