Defending the Tabasará River

Ngäbe communities have been resisting government proposals to build dams on the Tabasará River since the 1970s. On April 10, 1999, several Ngäbe were arrested following protests against a proposed 48-megawatt dam, and it was on this day that the affected communities formed the resistance movement Moviemiento 10 de Abril (M10).

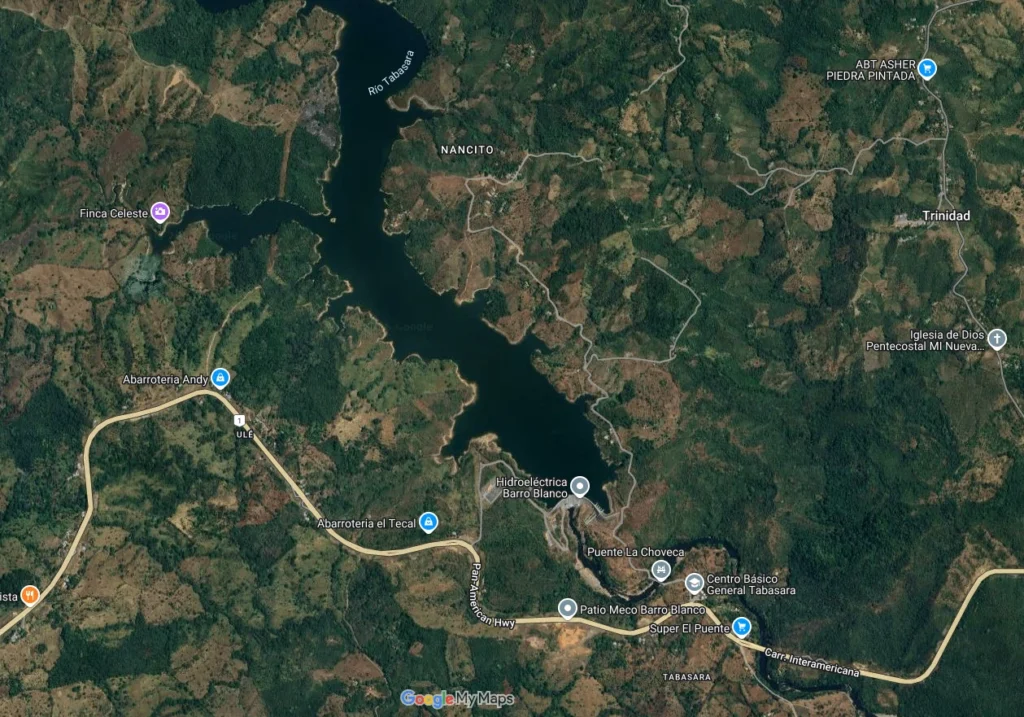

In 2007, the Panamanian government granted a concession to Generadora del Istmo (GENISA), a company owned by the prominent Honduran Kafie family, to build the 28.84-megawatt Barro Blanco dam on the Tabasará River in Chiriquí, western Panama. The project was financed through loans from three development banks, including the Dutch FMO and the German DEG, and was approved under the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) scheme—a UN carbon offset program that allows developed countries to invest in projects aimed at reducing carbon emissions in developing nations.

Construction of the Barro Blanco dam began in February 2011 and was completed in 2016, significantly impacting four Ngäbe communities living along the Tabasará River. The reservoir has submerged homes, farmland, and sacred sites—lands that hold cultural, economic, historical, and spiritual significance for these communities. The dam has altered the natural flow of the Tabasará River, negatively affecting local ecosystems and biodiversity. Fish populations, which are a vital food source for the Ngäbe, have declined, leading to reduced availability of protein.

The Ngäbe communities contend that their rights to free, prior, and informed consent were not respected during the planning and construction of the dam. Numerous protests and conflicts have arisen between the Ngäbe communities, the Panamanian government, and the companies involved in the dam’s construction, sometimes resulting in violent clashes and repression.

In response to human rights concerns, the government has withdrawn Barro Blanco from the Clean Development Mechanism scheme. Investigation panels have advised the development banks that funded the dam to publicly apologize for its impacts and ensure that affected communities receive compensation. To date, the Tabasará communities continue to fight for reparations.

Today, neither grandchildren nor granddaughters can [bathe] because if they go now, they get into the water and tomorrow they will have an itchy body because that water produces itching and allergies, and so for that not to happen we have to tell the children, no, don’t go into that water. Even so, they go and get in, but they suffer with their skin, with illnesses, and that is exhausting, it has been an exhausting struggle, and with the hydroelectric dam, everything is worse. We have nowhere to go, and we knew it was going to be like that, and that is why we did not want the hydroelectric dam to be built there.

— Weni

It can be an earthquake, it can be anything, a tsunami, but it happens, and it goes away. Unlike the Barro Blanco project, for us, it is a very terrible experience, because it is a project that is here to stay for 100 years. And it has changed our lives in the worst way. We are not free to move where we want. If there is no transportation, we can’t cross, and the reservoir is full of sediment. In other words, it’s a terrible thing for us to live this life since the floodgate was closed. So, we consider that our life has changed a lot because of the project, which was built for foreign interests and not for the communities as they said.

— Goejet