On December 11, 2025, Dennis Eduardo Lucas Amador forcefully invaded the farm of the Castrellóns, an Indigenous Ngäbe family from the community of Valle de Agua in Bocas del Toro province, Panama. He destroyed their crops, felled their trees, erected fences, and filled the property with roaming livestock. Lucas, a man with a criminal record who usually lives in Costa Rica, claims to be the rightful owner of the land, but a previous survey by the National Land Administration Authority (ANATI) suggests he is not.

Marta Villagra, the family’s matriarch, has lived and worked on her land for more than 70 years. She has endured on-and-off harassment from Lucas since 2003, and she lost her husband, Ricardo, after he was left traumatized by a violent eviction attempt in 2006.

She told IC, “We want peace and tranquillity in our homes. How much longer must we live like this?”

Despite numerous laws and constitutional articles which recognize Indigenous identities and guarantee Indigenous land rights, territorial conflicts are all too common in Panama. An apparent lack of political will, institutional weakness, racial discrimination, a Kafkaesque legal system, and a shambolic land registry are some of the factors in the state’s ongoing failure to uphold its human rights commitments.

Equally, legal definitions of private property – and all the bureaucracy they entail – have no historical precedent in Ngäbe culture, as Ricardo’s granddaughter, Olinda Castrellón explained:

“My grandfather, Ricardo Castrellón, thought about our family’s future. He left us a legacy. But unfortunately, due to our failure to adapt to the Western system, as we call it here in Panama, we find it difficult to understand some of the things the government says. As Indigenous people, our entire heritage was oral. However, in the Western system, everything is written down; everything is on paper. If you don’t have papers, you’re nothing.”

Prior to European colonization of the Americas, the Ngäbe were a dispersed, semi-nomadic tribe who practiced shifting agriculture across a substantial region corresponding to present-day western Panama and eastern Costa Rica. In the 20th century, however, permanent dwellings became the norm.

So it was that in 1955, Ricardo Castrellón and his brothers settled in Valle de Agua, practicing small-scale subsistence farming like their forebears. Life was peaceful and the community flourished. Ricardo’s family expanded with children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

But around 20 years ago, everything changed after a road was built through the community by the Panamanian government.

“A stranger arrived,” said Olinda, “and we say ‘stranger’ because we didn’t know him. And then, after that, he claimed to have the property deed to our land.”

The Castrellón family land is located within a so-called Annex Area of the Ngabe-Buglé Comarca – a semi-autonomous Indigenous region with significant rights to self-governance and self-determination. However, Annex Areas technically fall outside the boundaries of the Comarca, leaving them vulnerable to predatory land grabbers.

The special status of Annex Areas as Indigenous territories was recognized by Law 10 – the same 1997 law that established the Comarca – but the Panamanian government has yet to properly demarcate them.

In 2001, the World Bank loaned the Panamanian government $47.9 million to secure Indigenous land tenure in Annex Areas, but the bank’s inspection panel subsequently found their processes non-compliant with World Bank policies. Equally, Law 72, passed in 2008, also compels the government to demarcate and collectively title Annex Areas, but has not been fully complied with.

Feliciano Santos, who lives in Valle de Agua and coordinates a grassroots network of Indigenous land defenders – the Movement for the Defense of the Territories and Ecosystems of Bocas del Toro (MODETEAB) – told IC that the illegal appropriation of Indigenous lands in Panama is conducted in an organized way, that is, with the full awareness of the state and the collusion of local institutions.

“The speculation is rampant among a network of speculators and officials who divide up the profits once they manage to seize the land and sell it,” he said. “This is the reality that the Indigenous community is experiencing, and this is not limited to the Castrellón family case.”

“The main bad actor is the Panamanian state for ignoring the rights of Indigenous peoples and for failing to legally secure the lands and territories of the Annex Areas. This allows anyone from outside the region to come with the backing of an authority who certifies their claim, and then, with the help of a lawyer, obtain a map and register it with ANATI, who then registers it with the agrarian court and other judicial bodies. Then they go to the Public Prosecutor’s office and accuse us of inciting crime, of being invaders, and many of us are criminalized that way.”

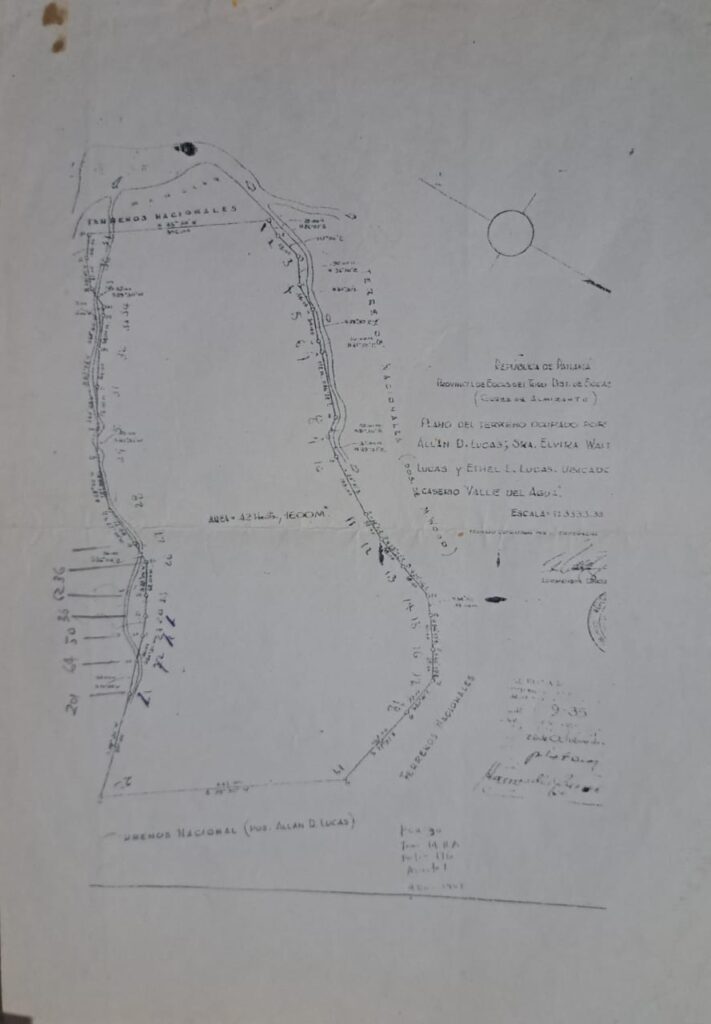

Certainly, Dennis Lucas has a long and shady history of conspiring with local officials and of fabricating documentation. In 2005, he arrived in Valle de Agua to conduct a survey of the area with a topographer, Juan Sergio Navarro, producing a hand-drawn sketch which appeared to indicate that the Castrellón family land belonged to Lucas’ neighbouring farm, Finca 30. On that basis, Lucas claimed that the Castrellóns were trespassing.

The following year, Lucas and an elected official from the nearby town of Almirante – the Corregidor Angelo ‘Magoo’ Grenald – visited the now elderly Ricardo Castrellón at his home and took him away in a state car to an office in the city of Changuinola. Although Ricardo could not read or write, he was persuaded to put his digital fingerprint to a document entitled ‘mutual agreement’, by which he yielded, without his knowledge, his family land – and his legacy – to a non-indigenous third party.

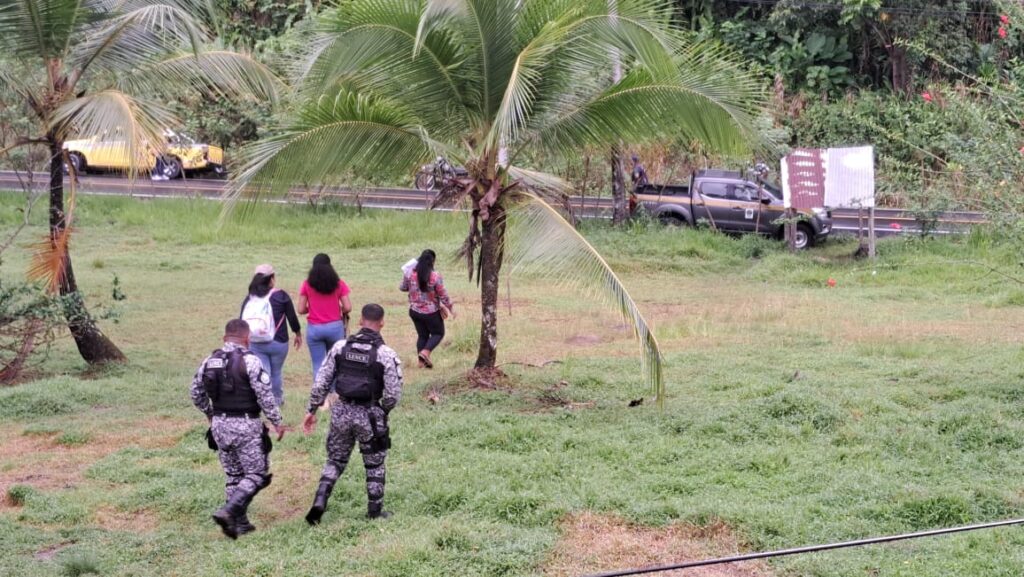

The full implications of the so-called ‘mutual agreement’ became clear on June 21, 2006, when Lucas arrived in Valle de Agua accompanied by Grenald and police officers, and proceeded to violently evict the Castrellón family and destroy their homes.

“When we were evicted, my grandfather lost his memory,” said Olinda. “For three days, he didn’t speak, he didn’t eat, because the eviction was so humiliating – so humiliating because they didn’t leave us a house. He was lost for three days. I remember it very clearly, like it was yesterday. My grandfather used to sit in a hammock, and every time we spoke to him, he wouldn’t respond.”

Soon after, however, the Mayor of Changuinola, Virginia Abrego Salinas, was compelled to account for the eviction. On June 29, 2006, she sent a letter to Olga Gólcher, then Minister of Government and Justice of Panama, stressing that the eviction had occurred “without any order or coordination with the Municipal Mayor’s Office.”

She wrote, “I proceeded to investigate the actions of the aforementioned Corregidor [Angelo Grenald]… and discovered that [the eviction] was carried out unilaterally… I have [therefore] ordered his immediate dismissal… and the suspension of the eviction process until the legitimacy of the land adjudication is defined.”

The Castrellóns were able to return to their land, but starting again was not easy. “We had to rebuild ourselves,” said Olinda. “We had to find that strength again to be able to continue doing our work.”

However, not everyone in the family was able to recover. Ricardo Castrellón, for one, was permanently changed by the experience.

“From that point on, until 2014, my grandfather was mentally unstable,” said Olinda. “It was a gradual process. He became ill and never returned to his normal life, passing away on March 20, 2014.”

Following the controversy of the failed eviction attempt, Lucas disappeared and left the family in peace. Olinda, who is a MODETEAB sub-coordinator, hesitated before presenting their case to the Interamerican Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) in Washington DC.

“Regardless of his disappearance, I was still worried,” she said. “But it wasn’t just the house that was demolished – that’s material damage – but my family, my grandparents, especially my grandmother, were humiliated because they were made to look like intruders, like invaders.”

Nonetheless, she presented details of the conflict to an IACHR thematic hearing on March 20, 2015. Following the commission’s recommendations, Panama’s National Land Administration Authority (ANATI) undertook a thorough survey of the area using Lucas’s sketch as a guide. On January 19, 2016, they issued a final report that concluded that the disputed land “lies outside Finca 30”.

In other words, the land did not belong to Lucas. However, Lucas himself persisted in claiming otherwise. In 2017, he returned from his hiatus to threaten the Castrellóns with a rifle.

“It was like something out of an old Western movie,” said Santos. “He was shooting continuously. I don’t know if he was only shooting into the air or at people, but he had everyone terrified.”

Lucas was reported to the authorities who then discovered unlicensed firearms on his property – a serious offense in Panama. He was subsequently found guilty of trafficking arms and sentenced to four years in prison.

Peace again returned to Valle de Agua, but it did not last. In 2023, Lucas returned and filed an agrarian protection lawsuit against the Castrellóns. With the financial backing of the Agricultural Development Bank (BDA) and the political backing of an agrarian judge, he renewed his claim to their land, cut down their trees, and destroyed 3 hectares of crops. So far, the courts have sided with him.

“How difficult it is,” said Olinda, “after that man evicted us, destroyed our house, and completely demoralized us, now we have to pay a contempt of court fine. We have to watch him drive through our property and it’s like nothing happens.”

“Sometimes I get frustrated, when I don’t see an answer, when I don’t see a way out, or when I see that time drags on longer every day. Now I understand how my grandfather felt. But we are not yet out of the running to fight.”

A few days after speaking to IC, the community obtained a preventative protection order from a Justice of the Peace. The order legally obliges Lucas to cease all forms of aggression and maintain a distance of at least 50 metres, but it is too soon to say whether the order will be effective.

Meanwhile, it remains unclear why Panama’s national government has not yet stepped in. On November 19, 2025, the IACHR received testimony regarding numerous violent abuses committed by Panamanian security forces against Indigenous peoples. Government representatives strongly denied those claims and insisted that Panama is a nation that adheres to international law and upholds Indigenous rights.

As the Castrellón case and countless others demonstrate, such declarations are hard to believe.

SOURCE: https://icmagazine.org/they-called-us-invaders-a-ngabe-familys-generational-struggle-for-home/